Evidence Based Interventions to Reduce Food Insecurity Peer Review

Abstract

Purpose of Review

To synthesise the research which has sought to evaluate interventions aiming to tackle children's food insecurity and the contribution of this research to evidencing the effectiveness of such interventions.

Recent Findings

The majority of studies in this review were quantitative, non-randomised studies, including accomplice studies. Issues with not-complete outcome data, measurement of elapsing of participation in interventions, and accounting for confounds are mutual in these evaluation studies. Despite the limitations of the current testify base of operations, the papers that were reviewed provide evidence for multiple positive outcomes for children participating in attended and subsidy interventions, inter alia, reductions in nutrient insecurity, poor wellness and obesity. Nevertheless, current evaluations may overlook key areas of impact of these interventions on the lives and outcomes of participating children.

Summary

This review suggests that the current prove base of operations which evaluates food insecurity interventions for children is both mixed and limited in scope and quality. In particular, the outcomes measured are narrow, and many papers take methodological limitations. With this in heed, a systems-based approach to both implementation and evaluation of food poverty interventions is recommended.

Introduction

Food insecurity is defined as "limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally acceptable and safety foods or express or uncertain ability to acquire adequate foods in socially acceptable ways (e.g. without resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing or other coping strategies)" [ane]. Despite experiencing relative wealth as nations, nutrient insecurity is an increasingly mutual miracle in some developed countries. Recent statistics bespeak that in 2016, 12.3% of households and 8% of children in America experienced food insecurity [two]. Similarly, xix% of UK children under 15 alive with a respondent who is moderately or severely food insecure and 10% live with a respondent who is severely nutrient insecure [3]. Whilst there is no current information on levels of children's nutrient insecurity in the Britain, eligibility for free school meals (which is based upon depression household income) can be used every bit a proxy measure. In 2018, xiii.6% of UK school children were eligible for free school meals [4], suggesting that nutrient insecurity may also be a significant result among UK children.

It is well-evidenced that food insecurity results in a restricted and less nutritionally acceptable diet [5]. This has wellness implications, as children who experience food insecurity are likely to accept poorer full general health, approximately twice as likely to have asthma and almost iii times as probable to have iron deficiency anaemia than food-secure children [half-dozen,7,eight]. Children who feel food insufficiency are also significantly more likely to exhibit behavioural problems, take difficulty getting on with other children [9] and experience anxiety and low [ix, ten]. Moreover, in 2015, just 33.ane% of UK school children eligible for free school meals achieved the primal attainment indicator at the end of secondary school, compared to 60.9% of more food-secure school children [11].

The bear witness base described provides a compelling case for interventions that seek to tackle children's nutrient insecurity, in order to minimise the health and social disparities betwixt children who experience food insecurity and those who do non. Footnote 1 These interventions take multiple formats; from attended interventions (e.g. school nutrient assistance and vacation clubs) to providing disadvantaged families with subsidies (e.yard. the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP). Even so, at that place is currently a lack of synthesis of the prove base which examines the effectiveness of these interventions, especially regarding the ways in which effectiveness is evaluated.

To our noesis, two systematic reviews of interventions to tackle children's food insecurity have been published to engagement. One is a rapid review recently published which only included interventions in the form of charitable breakfast clubs and holiday hunger projects in the UK [12••]. The other is a recent rapid review funded by the NIHR which explores the nature, extent and consequences of food insecurity amid children [13]. Withal, this review focused on quantitative outcomes of interventions where the food insecurity status of the sample has been measured and, therefore, only includes a very targeted and limited number of studies. With this in listen, the current review sought to produce a systematic review of the literature on interventions from developed countries which seek to tackle children's food insecurity, to proceeds a clear movie of the post-obit: (1) the ways in which food insecurity interventions are evaluated; and the quality of this evaluation and (2) the evidence base of operations of the affect of these interventions, in terms of positive outcomes for the targeted children.

Methods

Search Strategy

Online searches were conducted using three databases to ensure that the full latitude of relevant publications was identified. These databases were PsycINFO, Medline and Scopus. Key terms relating to nutrient insecurity interventions were used to identify a pool of potentially relevant papers for this review. These key words were the following: child* adolescent* "young people" "youth" "intervention" "vacation club" combined using the Boolean operator AND with whatever of the following words: "nutrient insecurity" OR "food poverty" OR "food insufficiency" OR "holiday hunger". Relevant articles were detected upwards until July 2018.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in this review, papers were required to evaluate interventions that seek to tackle food insecurity and to measure the outcomes specifically for children. Studies were besides required to take identify in a developed country as defined by the United Nations [xiv] and to be published in a peer-reviewed periodical. Papers were excluded if they only measured children'due south uptake of an intervention (eastward.k. a procedure evaluation) or if the outcome measures referred to households or families rather than children. They were also excluded if they were not published in English.

Identification of Relevant Papers

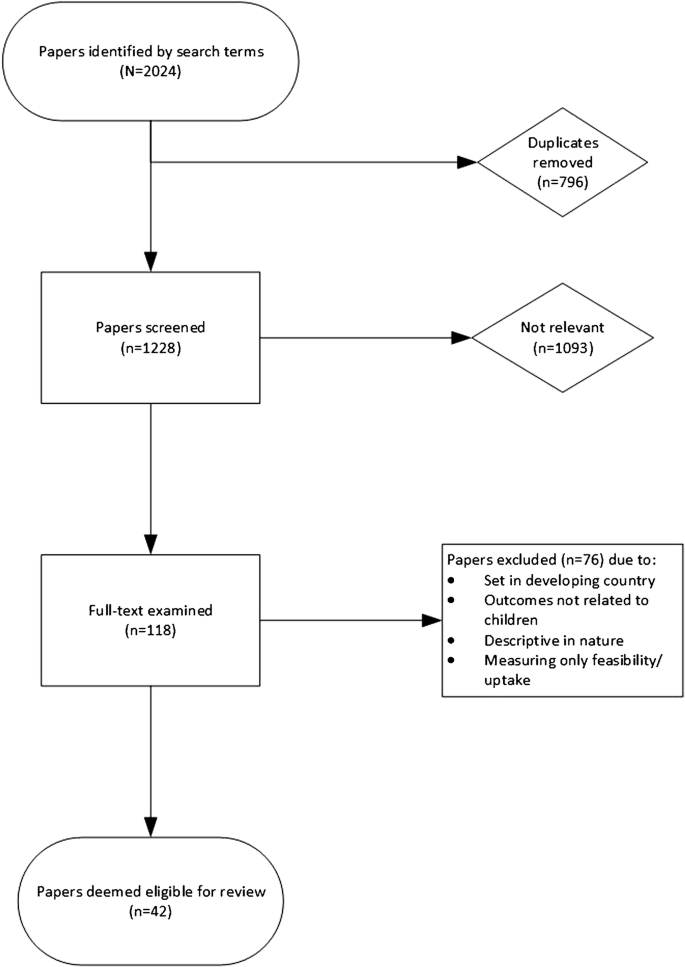

The process for identification of relevant papers tin can be seen in Fig. i. The showtime author screened the titles of all the search results to identify potentially relevant papers. When a championship was deemed relevant (or when relevance was ambiguous), the abstract was screened for eligibility to assess whether the paper met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full text was then read for all papers which either (a) met these criteria or (b) did not contain sufficient item in the abstract to assess eligibility.

Menstruation diagram of the identification process for papers included in this systematic review

Data Extraction

Data was extracted by the first author from 42 papers that met the eligibility criteria for this review. Data extracted was standardised beyond studies using a grade specifically adult to come across the aims of this review. Extracted data included author(s), date and place of publication, country of study, written report aim(s), type of intervention, target population of intervention, method of evaluation and the findings pertaining to kid outcomes of the intervention(southward). A summary of this data can be seen in Tables 1 and 2 for attended (in person) and subsidy-based interventions respectively. Footnote 2

Quality Cess

The offset author performed an cess of the quality of the terminal papers included in this review using the latest version of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [15]. This tool provides v questions to appraise the quality of studies with qualitative, quantitative or mixed methodologies. In line with the creating authors' guidance, scores for individual papers were not calculated. Instead, analysis was undertaken on the quality of the included papers collectively.

Results

The 42 papers included in this review were published between 2002 and 2018 and reported on studies conducted in the The states (n = 34), UK (n = four), Australia (n = 1), Canada (north = 1), Greece (n = 1) and New Zealand (n = 1). The interventions took multiple formats that tin can be categorised into two groups, attended (in-person) interventions and subsidy interventions. Kickoff, the means in which these papers evaluate food insecurity interventions are explored, as well every bit the quality of these papers. Next, the evidence base, as described in these papers, of the outcomes of these interventions for participating children is discussed.

The Kinds of Evaluation of Food Insecurity Interventions Taking Place

Interventions captured in this review prefer different approaches that aim to tackle separate aspects of food insecurity in club to achieve particular positive outcomes for children, and this, therefore, informs the kind of evaluation which takes identify. For example, school-based interventions that typically aim to tackle children not accessing an acceptable breakfast or luncheon and then examine the impact on children in the classroom (e.g. behaviour, educational achievement). Interventions that endeavor to increase consumption of fruit and vegetables measure out effectiveness in terms of achieving this aim, whilst ignoring any potential wider impacts that may impact positively (or negatively) on children's outcomes.

The research methods used in the papers included in this review are listed in Tables 1 and 2. At that place is a paucity of big-calibration RCTs to investigate the effectiveness of interventions for tackling children's food insecurity, and for upstanding reasons (such as withholding an intervention from individuals who it is believed would benefit), this would be hard to overcome. Several studies captured in this review utilise cohort data to overcome these ethical issues. Whilst this allows comparison between participants and other individuals of a similar demographic, there are other methodological limitations of this approach. For instance, as described in Dunifon and Kowaleski-Jones' evaluation of the Nation School Dejeuner Program (NSLP), differences in outcomes between eligible children who practise and exercise not participate in interventions may well be driven by unmeasured factors and pick bias [16]. To benumb the event of selection bias, equally well every bit issues of identification (where it is not always possible to assess participation), the cohort studies included in this review, particularly those which explore relationships between subsidy intervention participation and children's food insecurity and obesity, accept used a range of statistical methods [16,xvi,17,xix]. However, in that location is a lack of consensus as to which of these statistical methods is most appropriate for overcoming issues of bias inside data, and this makes it difficult to assess the robustness of findings reported in these papers.

Several of the studies detected by this review are experimental studies that provide valuable quantitative results on the outcomes of the interventions seeking to tackle children's food insecurity. However, these are often modest-calibration, with just parent-written report/cocky-report measures of outcomes, such as dietary intake [20,20,21,23].

When considering the quantitative articles in this review as a whole, information technology is apparent that at that place is a lack of longitudinal analyses which can meliorate unpack the causality of relationships between intervention participation and outcomes for children. The studies presented provide the beginning of an understanding of the possible benefits for children participating in food insecurity interventions. However, large-scale longitudinal studies which allow assessment of long-term outcomes and remove the potential confounds associated with group comparisons are strongly needed.

Qualitative studies have been conducted to gain service-user perspectives on food insecurity interventions and the positive benefits for children [24, 25, 26•, 27]. Whilst these studies play an of import role in evaluating these interventions, those captured in this review have predominantly utilised parents and stakeholders as participants, whereas children'due south voice is only included in a small proportion of these studies. In low-cal of this, future enquiry should seek to ensure that the voices of participating children and immature people are included in evaluation work, every bit those best placed to written report their own experiences [28].

Quality Assessment

Utilising the MMAT (2018) revealed that there was variation between the attended and subsidy interventions in the quality of the studies that were undertaken. For each of the groups, 24 papers were reviewed in full. Information technology is important to note that as the methods varied for the studies, the quality criteria also varied across the studies. Notwithstanding, examining the number of papers that met all five criteria associated with the particular study blueprint is useful as a fashion of exploring the overall quality of the evidence base. For the subsidy programmes, 95% of the papers met at least 3 of the quality criteria whilst a smaller number met the third (58%) and 4th (50%) quality criteria. For the attended programmes, there was less departure and more than consistency across studies in meeting the quality criteria (criteria ane = 75%, criteria 2 = 71%, criteria 3 = 83%, criteria four = 63%, criteria 5 = 79%.)

The majority of the studies (n = 32, 76%) were quantitative not-randomised studies defined as any quantitative studies estimating the effectiveness of an intervention or studying other exposures that practice non employ randomisation to allocate units to comparison groups [29]. Of these studies, the majority involved participants that were representative of the target population (91%); used appropriate measurements regarding both the effect and intervention (96%); and involved interventions that were administered as intended (91%). All the same, merely 70% provided complete outcome information (with very few measuring duration or level of participation in the intervention), and only 52% accounted for confounders in the blueprint and assay. Of the remaining studies, three were qualitative, v were quantitative randomised controlled trials and 2 were mixed-methods. Whilst RCTs are the gold standard of intervention evaluation, those captured in this review were typically of poor quality (meeting a maximum of three criteria), with inadequate reporting or implementation of randomisation, a lack of data of blinding of the experimenters and some problems with baseline group differences. This overview indicates that designing a high-quality study that meets all quality criteria on this topic is challenging.

The Show for Positive Outcomes for Children Targeted past Food Insecurity Interventions

Attended Interventions

Xx-four papers included in this review related to attended interventions, including schoolhouse nutrient help (breakfast and luncheon provision; north = 13), vacation clubs (n = 3), interventions including diet education (n = 7) and gardening clubs (n = 1). A summary of these papers tin be found in Table 1.

School Food Aid

Iv papers assessed the impact of school nutrient assistance (as a group of interventions) on children. It was found that US schoolhouse food assistance can significantly amend educational difficulties, where the relationship between household food insecurity and educational difficulties disappears for children who participate [30]. It has as well been found that nutrient-insecure girls participating in the United states of america's Schoolhouse Breakfast Programme (SBP), National Schoolhouse Lunch Program (NSLP) or Food Stamp Programme (FSP—or all iii) have a reduced risk of obesity compared to not-participating food-insecure girls. Even so, there was no effect of participation on risk of obesity for boys [31]. Moreover, participation in U.s.a. school meals alongside WIC (Women, Infants and Children) and/or SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme) has been associated with increased risk of obesity for food-secure children, but not for food-insecure children [32]. Lastly, show has been plant that school-based nutrient assistance can reduce the odds of children experiencing nutrient insecurity among loftier-risk (border colonias) populations [33].

5 papers evaluated the impact of school breakfast interventions on children's outcomes, with US studies finding that they can reduce the disparity in breakfast consumption betwixt food-secure and food-insecure children and reduce children'south food insecurity Footnote 3 [34, 35]. U.k. stakeholders besides perceive benefits of universal gratuitous school breakfast, including alleviating hunger and improving health outcomes, as well as providing social, behavioural and educational benefits [25]. Whilst one paper reported that UK stakeholders have concerns about universal free schoolhouse breakfast increasing obesity [25], no associations between participation in United states breakfast in the classroom and obesity have been plant [36]. Research has failed to notice evidence of gains in academic functioning in relation to breakfast in the classroom in the US [36]. All the same, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of UK school breakfast provision reported that post-intervention, participating children demonstrated significantly improved concentration, skipped fewer classes and ate fruit for breakfast more than when compared to control children [37•]. Mail service-intervention, participating chief school children had higher rates of borderline/abnormal conduct and behavioural difficulties compared to the control group, and participating secondary school children more than frequently had deadline/aberrant prosocial scores than the control group. Nevertheless, these findings were not supported by all analyses, and a lack of baseline assessment prevents conclusions being drawn from these findings[37•].

Four papers evaluated the effects of participating in schoolhouse luncheon interventions. Participation in the US NSLP has been associated with increased odds of hunger [33], a health limitation, and lower maths test scores, likewise equally increased odds of externalising behaviour [16]. However, when comparing outcomes of siblings, one of whom does not participate in the NSLP, in that location are no associations of NSLP participation with negative child outcomes, suggesting that these increased odds may be a production of familial factors non controlled for elsewhere [16]. A further paper evaluated the impact of the NSLP, whilst controlling for methodological issues, such as participants self-selecting to participate in the NSLP (which has been suggested every bit an explanation for the positive relationship of participation with poor health), and using comparison groups of participants who were ineligible for the intervention [17]. Using this approach suggests that the NSLP reduces incidences of poor wellness and obesity. Other inquiry has besides explored whether the human relationship betwixt BMI and obesity is modified by participation in the NSLP [38]. However, no pregnant relationship between household nutrient insecurity and child BMI was plant among NSLP participants or not-participants.

Holiday Clubs

3 qualitative papers were detected which evaluated summer holiday clubs that offering gratuitous food alongside other enrichment activities, such as physical activity, stories and crafts. Both staff and attendees at United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland holiday breakfast clubs and other vacation clubs report nutritional (due east.yard. more than substantial and varied breakfast, trying new foods, attenuating hunger), social (e.chiliad. removing social isolation and providing new interactions) and financial benefits to attending these clubs [26•, 27]. Lastly, parent attendees of a Us lunch in the library scheme described that the intervention allowed their children to socialise, and they valued the other enrichment opportunities this intervention provided [24].

Diet Education

Half-dozen papers reported outcomes for children who had participated in nutrient insecurity interventions involving nutrition instruction, with two finding no significant effects. One such newspaper explored the addition of six sessions of nutrition education to the Child's Café Programme, a free meal initiative in the U.s.a., using an RCT [22]. No significant effect was found in the intervention on children's vegetable consumption, and intervention children had significantly higher sodium intake mail service-intervention than control children. Even so, it should be noted that the authors written report that there were problems with the acceptability of nutrition education classes. Another experimental paper assessed an intervention in New Zealand which offered nutrition education, fruit and vegetable tasting and encouraged growing and cooking vegetables and other salubrious meals [21]. No significant effect of intervention was found on nutrient intake, but children consumed significantly fewer highly processed snack foods post-intervention. In that location were increases in fruit and vegetable consumption at half dozen months mail-intervention, merely significance could not be tested due to drib out rates.

4 papers reported positive outcomes of nutrition education food insecurity interventions. A small-scale experimental study explored the effects of the Food and Fun intervention, an eight-week curriculum of nutrition education aslope education nigh physical activity, tasting healthy foods, complimentary meals and physical activeness [23]. The authors study that children'due south fruit and vegetable consumption, as well as their levels of physical activity, significantly increased afterwards the intervention. A similar intervention has as well been implemented among sheltered homeless children, called Cooking, Good for you Eating, Fitness and Fun (CHEFF). A qualitative report plant that child attendees showed some increased willingness to try different foods, developed increased liking of new foods and intentions to change health behaviours [39]. The Brighter Bites intervention in the Us too has a nutrition educational activity component, which is delivered alongside provision of costless fresh produce which is redirected from nutrient waste matter [40]. Parents reported that their child'southward intake of fresh produce increased after participating, with most reporting that the nutrition teaching component was effective. Similarly, diet education has been integrated into a free-school meal intervention in low SES schools in parts of Greece [41]. Here, provision of a gratuitous meal, education about a salubrious diet and concrete activity, as well as cooking demonstrations for parents, resulted in significant increases in consumption of multiple healthful foods, and some movement towards a Mediterranean diet design, which is suggested to have health benefits.

Nutrition education has also been added in to subsidy interventions that seek to tackle nutrient poverty, such as the US Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme (SNAP-Ed). One paper evaluated the long-term effects of SNAP-Ed participation on children's food insecurity in an RCT [42]. It was constitute that at that place was no significant modify in children's nutrient insecurity condition in comparison to a control group who received SNAP benefits alone. The authors highlight that it is likely that children are buffered from the main effects of household food insecurity (which was lowered by the intervention) and that children's food insecurity was low in the sample at baseline.

Community Gardening

1 paper explored the utility of a community gardening intervention for increasing vegetable intake and reducing nutrient insecurity among child attendees. Afterward participation, the number of children consuming vegetables several times a mean solar day increased substantially, but there was no significant change in the number of meals children missed [20].

Subsidy Interventions

Xx-3 papers identified in this review explored the impact of subsidy interventions on children's outcomes. These included papers evaluating the Women, Infants and Children intervention (northward = 4), SNAP (previously known as the Nutrient Stamp Programme; FSP) (north = 14), and other subsidy interventions (n = 6). A summary of these papers can exist found in Table two.

Women, Infants and Children

WIC is a short-term multi-faceted US intervention that seeks to alleviate nutritional risk among low-income women, infants and children in club to protect their health. It does this by providing nutritious foods, information on salubrious eating and referrals to additional healthcare (including immunisation and screening) [43]. Four papers evaluated the possible effects of WIC on children, with the get-go suggesting that WIC reduces the prevalence of child food insecurity [44]. Further research has found that among WIC eligible infants, claimers had a significantly lower probability of being underweight, short or being rated as having poorer health than infants not claimed for due to access issues [45]. This, combined with the fact that infants of WIC claimants were of comparable weight and length to national averages, suggests that WIC may well attenuate nutritional and growth deficits amidst participants. Indeed, a further study institute that WIC participation attenuates child health risks associated with family stressors, with WIC participants having higher odds of well child status and lower odds of poorer health status and overweight compared to eligible non-participants [46]. Lastly, WIC participation (along with SNAP and free school meals) has been associated with increased BMI and waist circumference for food-secure but not nutrient-insecure children [32].

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

SNAP is a U.s. intervention that provides food-purchasing assistance to low-income families and individuals [43]. The outcomes of SNAP participation for children were assessed in fourteen papers included in this review, making it the most extensively evaluated intervention captured. In terms of educational attainment, participation has been constitute to improve girls' mathematics and reading scores [47] and moderate the negative relationship between deprivation and children'southward class attainment [48]. In terms of wellness outcomes, the show suggests that participation reduces poor health among food-insecure children [seven, 18].

Testify as to whether SNAP participation affects weight status or decreases children's food insecurity is mixed. For example, when operating under the proper noun the "Food Stamp Program" (FSP), participation over a 5-year menses was associated with decreased odds of overweight amidst young boys and increased odds among immature girls, with no associations found for older children [49]. However, the authors acknowledge that nutrient insecurity was not controlled for in these analyses. In other research, FSP participation has been associated with a reduced take a chance of overweight among food-insecure girls compared to non-participating food-insecure girls, although no significant effects were found for boys [31], and SNAP participation (along with WIC and costless school meals) has been associated with increased BMI and waist circumference for food-secure but not food-insecure children [32]. Moreover, whilst i study found that, when controlling for financial stress, participation decreases both weight status and severity of overweight among children [50], a further study (which did not control for fiscal stress) found no relationship between food insecurity and BMI amidst SNAP users or not-users [38].

Findings on the furnishings of SNAP participation on children'due south food insecurity are also mixed. Some studies take suggested that participation in SNAP is associated with decreased odds of child food insecurity amid a full general US population and border colonias [18, 51, 52], also every bit the proportion of children not eating enough [53]. However, i study reports that at that place is no relationship between SNAP participation and children's nutrient insecurity [54] whilst a 2d reports that although SNAP participation reduces household food insecurity, it increases food insecurity amidst children [55].

Other Subsidy Interventions

A like intervention to WIC is the Keeping Infants Nourished and Developing (KIND) intervention. KIND is a collaboration between primary care physicians and a food depository financial institution, providing supplementary babe formula, educational materials, and clinic and community resource. KIND intervention infants were more than likely to complete a full gear up of well-babe healthcare visits than non-users, but there was no meaning difference in weight-for-length between users and non-users [56], suggesting possible attenuation of nutritional deficits.

Two papers included in this review evaluated the Summer Electronic Do good Transfer for Children (SEBTC), which is an extension of the standard SNAP provision. This intervention provides eligible families with an additional $60 per eligible child each month during the summertime, when demands on family finances are greater. These papers reported significantly lower levels of food insecurity amid randomly allocated participants, compared to a control grouping, besides as moderate improvements in children'southward fruit, vegetable and dairy consumption [57, 58].

The Child and Adult Intendance Food Program (CACFP) is an American intervention that reimburses child care providers for meals and snacks consumed. One study in this review explored relationships between CACFP participation and overweight status, food consumption and food insecurity [59]. It was institute that participation may reduce the prevalence of overweight amid low-income children (although the authors highlight the detected effect was also minor to exist of note) and moderately increases consumption of vegetables and milk.

Another subsidy intervention detected in this review is the Individual Evolution Account (IDA) savings programme, which matches every USD saved with farther two. It also provides financial education and grooming on budgeting and credit repair and other asset-specific training. The enquiry presented in this review institute no significant difference in children'southward food insecurity between those newly enrolled on the plan and those who had graduated from the programme [60].

The last subsidy intervention detected in this review was a community-supported agriculture intervention, where low-income families tin purchase a share of a farmer'due south harvest at a 50% disbelieve and then receive deliveries of fresh fruit and vegetables throughout the flavour. Whilst participating children had higher fruit and vegetable intake than the national boilerplate and were more probable to meet recommendations for consumption, there was no significant difference in consumption between the summer and winter when they were not receiving fresh produce [61]. Therefore, the study does not evidence a positive consequence of the intervention on consumption, instead it is likely that those who chose to participate had college consumption of fruit and vegetable consumption.

Discussion

This review has examined the existing evidence base pertaining to interventions that have attempted to address children's nutrient insecurity. The review has highlighted that the existing evidence base about what works in terms tackling children's food insecurity and the resultant potential for delivering positive impacts for children is problematic due to issues including the following: interventions having ill-defined aims; a lack of robust evaluation approaches; a lack of consistency in measures (both in terms of food insecurity and intervention outcomes); measurement of a restricted issue or outcomes; and a lack of explanatory value. There is besides considerable variation in the methods utilised to testify the effectiveness of the interventions as some claim a wide range of positive outcomes which are measured qualitatively (e.g. self-reports) whilst other interventions are evaluated using very narrow criteria (due east.g. vegetable consumption, number of healthcare visits) rather than examining the broader touch on the family in the long term. This supports concerns raised in other literature, where concepts like food insecurity are used likewise narrowly, with also strong a focus on outcomes of nutrient quantity or nutrient intake [12••]. There is a lack of robust evidence of outcomes, such every bit that derived from RCTs. All the same, as outlined elsewhere, conducting such research has numerous methodological issues, particularly when related to public wellness interventions where implementation is rapid [37•, 62].

Several of the papers reported in this review seek to evaluate the touch of interventions on children's food insecurity. However, food insecurity is a multi-faceted construct, with implications for nutrient quality, multifariousness and quantity [1]. Furthermore, in that location is no i internationally agreed mensurate of nutrient insecurity. For example, the US regime routinely collect information on nutrient insecurity using the United states of america Department for Agriculture Nutrient Security Scale, with possible outcomes ranging from high to marginal, low and very low food security. Meanwhile, the UK government does not collect such data or have an agreed standardised measure in place. Consistent measurement of food insecurity is needed not but to assess the calibration and nature of the issue but also to permit robust development of interventions to address food insecurity.

Additionally, there is considerable variation in the design of interventions, with some designed to alleviate food insecurity, whilst others are designed to tackle problems that are (assumed) consequences of food insecurity and nutrient scarcity (e.one thousand. increasing consumption of fruit and vegetables, developing food confidence, providing nutritional educational activity). Moreover, whilst attended interventions, such as vacation clubs, are increasingly prevalent, this review has found that they can exist poorly described with very limited evaluation, and in that location is a paucity of comprehensive information on how, where and with whom these interventions are implemented [12••]. Typically, the interventions represented in this review lack a articulate theory of change which outlines how and why the intervention might deliver the intended outcomes [63, 64]. It is therefore recommended that firstly, future inquiry seeks to more demonstrate that interventions touch on food insecurity. Secondly, plans for interventions must outline how and why the intervention will convalesce food insecurity, and therefore achieve the resultant impacts. Having done this, information technology will then be possible to identify how reduced food insecurity impacts on delivering detail positive outcomes for children.

The review has too revealed that there are two main strategies that have been adopted in attempts to address children's nutrient insecurity, which are described here equally attended and subsidy interventions. These two strategies provide different possibilities for supporting families experiencing food insecurity which are also important to notation. Subsidy programmes provide families with more than flexibility to make decisions about how the additional resources they are provided with tin can best be utilised within individual families, merely they have the disadvantage of potentially further stigmatising families who are divers by their depression socio-economic status [65]. In contrast, the attended programmes tin exist devised in ways where children access back up in spaces and places that they already attend (e.g. school) as universal provision which reduces the risk of children beingness further stigmatised [26•]. Whilst it appears that both these strategies may result in positive outcomes, it is non clear the extent to which families experiencing food insecurity are influencing the design of the interventions that they are the beneficiaries of. The disadvantage of this arroyo is that families do non have the opportunity to ensure that interventions best encounter their complex needs in a holistic style. Another recommendation arising from this review is therefore that systems-based approaches to tackling food insecurity are needed if real alter is to be both delivered and evidenced in the long term.

Conclusions

In summary, this review has synthesised the inquiry that evaluates interventions to tackle children's food insecurity and found this evidence base to be both mixed and lacking in robustness. In gild to promote effective interventions to tackle children's food insecurity, interventions should exist grounded in theory of alter and take a systems-based arroyo to both implementation and evaluation of these interventions. To do this, measurement of food insecurity must be standardised and universally implemented, ensuring that such interventions are coming together their primary aim also equally the wide variety of other positive outcomes such interventions have the potential to achieve.

Change history

-

04 March 2019

The original version of this commodity unfortunately contained mistakes in Tables captions.

Notes

-

Information technology is noted that children can move in and out of these binary groupings and may do then several times across their babyhood.

-

Some papers are listed in both Tables one and ii equally they evaluate both attended and subsidy interventions.

-

This paper reports outcomes in terms of changes in low and very low nutrient security as measured by the USDA Food Security Scales. For consistency and ease of estimation, findings that accept been anchored in relation to changes in nutrient security take been used throughout this review.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

-

Taylor A, Loopstra A. Likewise poor to consume: food insecurity in the Uk, London; 2016.

-

United states Department of Agriculture: Economic Enquiry Service. Nutrient security in the United states: key statistics and graphics; 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assist/food-security-in-the-u.s.a./key-statistics-graphics.aspx#children.

-

The Food Foundation. In: New evid. child food insecurity Britain; 2017. https://foodfoundation.org.uk/new-evidence-of-kid-food-insecurity-in-the-uk/.

-

Section for Education. Schools, pupils and their characteristics: Jan 2018; 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/organisation/uploads/attachment_data/file/719226/Schools_Pupils_and_their_Characteristics_2018_Main_Text.pdf. Accessed 16 Aug 2018.

-

Molcho Grand, Gabhainn Due south, Kelly C. Food poverty and health amidst schoolchildren in Ireland: findings from the Wellness Behaviour in Schoolhouse-aged Children (HBSC) study. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:364–70.

-

Eicher-Miller H, Mason A, Weaver C, Boushey CJ. Food insecurity is associated with iron deficiency anemia in U.s.a. adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;xc:1358–71.

-

Cook JT, Frank DA, Levenson SM, Neault NB, Heeren TC, Black MM, et al. Child food insecurity increases risks posed by household food insecurity to young children's wellness. J Nutr. 2006;136:1073–half dozen.

-

Kirkpatrick SI, McIntyre L, Potestio ML. Child hunger and long-term agin consequences for health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:754–62.

-

Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA Jr. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children's cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108:44–53.

-

Melchior M, Chastang J-F, Falissard B, Galéra C, Tremblay RE, Côté SM, et al. Food insecurity and children's mental wellness: a prospective birth cohort study. PLoS 1. 2012;vii:e52615.

-

Department for Didactics. National statistics: GCSE and equivalent attainment by pupil characteristics; 2014. https://www.gov.u.k./regime/statistics/gcse-and-equivalent-attainmentby-pupil-characteristics-2014. Accessed x Aug 2018.

-

•• Lambie-Mumford H, Sims L. 'Feeding hungry children': the growth of charitable breakfast clubs and holiday hunger projects in the UK. Child Soc. 2018;32:244–54 This is the kickoff review to synthesise the knowledgebase on United kingdom charitable responses to children's nutrient insecurity.

-

Aceves-Martins M, Cruickshank Yard, Fraser C, Brazzelli M. Child food insecurity in the United kingdom: a rapid review. Public Health Res 2018;6(13).

-

Un. World economic state of affairs and prospects; 2018. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wpcontent/uploads/sites/45/publication/WESP2018_Full_Web-1.pdf. Accessed 05 July 2018.

-

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fabregues South, et al. Mixed methods appraisement tool (MMAT) version 2018 user guide; 2018. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/due west/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf. Accessed 27 Sept 2018.

-

Dunifon R, Kowaleski-Jones L. The influences of participation in the National School Lunch Program and nutrient insecurity on child well-being. Soc Serv Rev. 2003;77:72–92.

-

Gundersen C, Kreider B, Pepper J. The impact of the National School Lunch Program on child wellness: a nonparametric premises analysis. J Econ. 2012;166:79–91.

-

Kreider B, Pepper JV, Gundersen C, Jolliffe D. Identifying the effects of SNAP (nutrient stamps) on child health outcomes when participation is endogenous and misreported. J Am Stat Assoc. 2012;107:958–75.

-

Gundersen C, Kreider B, Pepper JV. Partial identification methods for evaluating food help programs: a case study of the causal impact of snap on food insecurity. Am J Agric Econ. 2017;99:875–93.

-

Carney PA, Hamada JL, Rdesinski R, Sprager L, Nichols KR, Liu BY, et al. Touch on of a community gardening project on vegetable intake, food security and family unit relationships: a community-based participatory research written report. J Customs Health. 2012;37:874–81.

-

Munday 1000, Wilson M. Implementing a health and wellbeing programme for children in early childhood: a preliminary report. Nutrients. 2017;9. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9091031.

-

Dave JM, Liu Y, Chen T-A, Thompson DI, Cullen KW. Does the Kids Café Plan's nutrition education better children's dietary intake? A pilot evaluation study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50:275–282.e1.

-

Racine EF, Coffman MJ, Chrimes DA, Laditka SB. Evaluation of the Latino food and fun curriculum for depression-income Latina mothers and their children: a pilot report. Hisp Wellness Care Int. 2013;xi:31–7.

-

Bruce JS, De La Cruz MM, Moreno G, Chamberlain LJ. Lunch at the library: test of a community-based approach to addressing summertime nutrient insecurity. Public Wellness Nutr. 2017;xx:1640–9.

-

Harvey-Golding L, Donkin LM, Defeyter MA. Universal free schoolhouse breakfast: a qualitative process evaluation according to the perspectives of senior stakeholders. Front Public Health. 2016;4:161.

-

• Defeyter MA, Graham PL, Prince Thousand. A qualitative evaluation of vacation breakfast clubs in the UK: views of adult attendees, children, and staff. Front Public Health. 2015;three:199 This is the only qualitative paper included in this review which triangulates the opinions of staff and attendees at a community intervention to tackle children'south nutrient insecurity. Equally attendees voices are critical in evaluative work, this is an of import paper.

-

Graham PL, Crilley East, Stretesky Atomic number 82, Long MA, Palmer KJ, Steinbock Due east, et al. School holiday food provision in the U.k.: a qualitative investigation of needs, benefits, and potential for development. Front Public Health. 2016;4:172.

-

Fram MS, Ritchie LD, Rosen N, Frongillo EA. Child experience of food insecurity is associated with kid nutrition and concrete action. J Nutr. 2015;145:499–504.

-

Higgins JP, Greenish S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley Online Library; 2008.

-

Roustit C, Hamelin A-M, Grillo F, Martin J, Chauvin P. Nutrient insecurity: could schoolhouse food supplementation help break cycles of intergenerational transmission of social inequalities? Pediatrics. 2010;126:1174–81.

-

Jones SJ, Jahns L, Laraia BA, Haughton B. Lower risk of overweight in school-aged food insecure girls who participate in nutrient assistance: results from the panel study of income dynamics kid evolution supplement. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:780–iv.

-

Kohn MJ, Bong JF, Grow HMG, Chan G. Food insecurity, nutrient aid and weight status in US youth: new evidence from NHANES 2007–08. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9:155–66.

-

Nalty CC, Sharkey JR, Dean WR. School-based nutrition programs are associated with reduced child food insecurity over time among Mexican-origin mother-child dyads in Texas edge colonias. J Nutr. 2013;143:708–13.

-

Khan S, Pinckney RG, Keeney D, Frankowski B, Carney JK. Prevalence of nutrient insecurity and utilization of food assistance plan: an exploratory survey of a Vermont middle school. J Sch Health. 2011;81:15–20.

-

Fletcher JM, Frisvold DE. The relationship betwixt the school breakfast programme and food insecurity. J Consum Aff. 2017;51:481–500.

-

Corcoran SP, Elbel B, Schwartz AE. The consequence of breakfast in the classroom on obesity and academic functioning: evidence from New York Metropolis. J Policy Anal Manag. 2016;35:509–32.

-

• Shemilt I, Harvey I, Shepstone L, Swift L, Reading R, Mugford Chiliad, et al. A national evaluation of school breakfast clubs: evidence from a cluster randomized controlled trial and an observational analysis. Kid Care Wellness Dev. 2004;30:413–27 This is one of a small number of RCTs captured in this review. It exemplifies the difficulties with conducting RCTs with public health interventions, and makes a clear statement about the necessary policy changes to overcome such difficulties.

-

Nguyen BT, Ford CN, Yaroch AL, Shuval K, Drope J. Food security and weight status in children: interactions with food assistance programs. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:S138–44.

-

Rodriguez J, Applebaum J, Stephenson-Hunter C, Tinio A, Shapiro A. Cooking, Healthy Eating, Fitness and Fun (CHEFFs): qualitative evaluation of a diet pedagogy plan for children living at urban family homeless shelters. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:S361–7.

-

Sharma SV, Upadhyaya 1000, Bounds One thousand, Markham C. A public health opportunity plant in food waste. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;xiv. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.160596.

-

Kastorini CM, Lykou A, Yannakoulia M, Petralias A, Riza E, Linos A. The influence of a school-based intervention program regarding adherence to a good for you diet in children and adolescents from disadvantaged areas in Greece: the DIATROFI study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70:671–7.

-

Rivera RL, Maulding MK, Abbott AR, Craig BA, Eicher-Miller HA. SNAP-Ed (supplemental nutrition assistance program-education) increases long-term food security amid Indiana households with children in a randomized controlled study. J Nutr. 2016;146:2375–82.

-

United States Department of Agronomics: Food and Nutrition Service. Women, infants, and children (WIC); 2018. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/women-infants-and-children-wic.

-

Kreider B, Pepper JV, Roy One thousand. Identifying the effects of WIC on food insecurity among infants and children. South Econ J. 2016;82:1106–22.

-

Black MM, Cutts DB, Frank DA, et al. Special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children participation and infants' growth and wellness: a multisite surveillance study. Pediatrics. 2004;114:169–76.

-

Black MM, Quigg AM, Melt J, et al. WIC participation and attenuation of stress-related child health risks of household food insecurity and caregiver depressive symptoms. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:444–51.

-

Frongillo EA, Jyoti DF, Jones SJ. Nutrient stamp program participation is associated with amend bookish learning amid school children. J Nutr. 2006;136:1077–80.

-

Beharie N, Mercado Grand, McKay 1000. A protective clan between SNAP participation and educational outcomes among children of economically strained households. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2017;12:181–92.

-

Gibson D. Long-term food stamp programme participation is differentially related to overweight in young girls and boys. J Nutr. 2004;134:372–9.

-

Burgstahler R, Gundersen C, Garasky S. The supplemental nutrition assistance plan, financial stress, and childhood obesity. J Agric Resour Econ. 2012;41:29–42.

-

Mabli J, Worthington J. Supplemental nutrition help program participation and child nutrient security. Pediatrics. 2014;133:610–nine.

-

Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Nalty CC. Child hunger and the protective effects of supplemental nutrition assistance programme (SNAP) and alternative food sources amid Mexican-origin families in Texas border colonias. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-13-143.

-

Gundersen C, Kreider B, Pepper J, Tarasuk V. Food help programs and food insecurity: implications for Canada in lite of the mixing trouble. Empir Econ. 2017;52:1065–87.

-

Nalty CC, Sharkey JR, Dean WR. Children'due south reporting of food insecurity in predominately food insecure households in Texas edge colonias. Nutr J. 2013;12:15.

-

Zhang J, Yen ST. Supplemental diet assistance program and food insecurity amid families with children. J Policy Model. 2017;39:52–64.

-

Beck AF, Henize AW, Kahn RS, Reiber KL, Young JJ, Klein MD. Forging a pediatric main intendance–community partnership to support food-insecure families. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e564–71.

-

Collins AM, Klerman JA. Improving nutrition past increasing supplemental nutrition assistance program benefits. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:S179–85.

-

Klerman JA, Wolf A, Collins A, Bell Southward, Briefel R. The effects the summertime electronic benefits transfer for children demonstration has on children's nutrient security. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2017;39:516–32.

-

Korenman S, Abner KS, Kaestner R, Gordon RA. The Child and Adult Care Food Program and the nutrition of preschoolers. Early on Kid Res Q. 2013;28:325–36.

-

Loibl C, Snyder A, Mountain T. Connecting saving and food security: evidence from an asset-building program for families in poverty. J Consum Aff. 2017;51:659–81.

-

Hanson KL, Kolodinsky J, Wang W, Morgan EH, Jilcott Pitts SB, Ammerman Every bit, et al. Adults and children in low-income households that participate in cost-offset community supported agriculture have high fruit and vegetable consumption. Nutrients. 2017;9. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070726.

-

Tapper G, Murphy S, Moore L, Lynch R, Clark R. Evaluating the costless school breakfast initiative in Wales: methodological issues. Br Food J. 2007;109:206–15.

-

W.One thousand. Kellogg Foundation. Using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation & activity logic model evolution guide. Michigan; 2001. https://world wide web.bttop.org/sites/default/files/public/W.K.%20Kellogg%20LogicModel.pdf. Accessed 02 Nov 2018.

-

Kubisch AC, Fullbright-Anderson K, Connell JP. Evaluating community initiatives: a progress report. New approaches to eval. community initiat. vol. 2 Theory, meas. anal. Washington, DC: Aspen Establish; 1998. p. 1–13.

-

Reutter LI, Stewart MJ, Veenstra Thousand, Beloved R, Raphael D, Makwarimba E. "Who do they think nosotros are, anyhow?": perceptions of and responses to poverty stigma. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:297–311.

Author information

Affiliations

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Clare E. Holley and Carolynne Stonemason declare that they take no disharmonize of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This commodity does not contain any studies with human being or brute subjects performed by any of the authors.

Boosted data

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: Tables 1 and 2 captions were corrected.

This article is role of the Topical Collection on Maternal and Childhood Nutrition

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were fabricated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Holley, C.E., Mason, C. A Systematic Review of the Evaluation of Interventions to Tackle Children'south Food Insecurity. Curr Nutr Rep 8, 11–27 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-019-0258-1

-

Published:

-

Consequence Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-019-0258-i

Keywords

- Child

- Food insecurity

- Hunger

- Intervention

- Evaluation

arterburnwhiressawd.blogspot.com

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13668-019-0258-1

0 Response to "Evidence Based Interventions to Reduce Food Insecurity Peer Review"

Post a Comment